The insurance regulator has repeatedly emphasised the importance of expanding insurance coverage in rural areas through regulations in 2005, 2015, 2020, and most recently in 2024. Although insurance companies have assured IRDAI of adopting suitable local measures, rural insurance penetration remains low. Despite IRDAI’s consistent focus on rural outreach and setting targets for the rural and social sectors, motor third-party pools, and others, tangible progress in implementation has been limited.

In India, there are 57 insurance companies offering life, general, and specialised lines of business, along with several reinsurance firms, premium management institutions for insurance expertise, and both international and domestic insurance distribution networks. These organisations are staffed by an experienced, knowledgeable, and skilled workforce at various levels. Usually, any article about the rural sector emphasises that India has a substantial rural market, with opportunities centred on distributing financial products, including insurance. Despite the presence of capable insurers and distributors on one side and a large uninsured population eager to access insurance on the other, the insurance penetration remains very low. Notably, only crop insurance under the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) accounts for a significant share of rural insurance coverage.

Then, what are the main challenges and the efforts required in terms of product, pricing, and distribution?

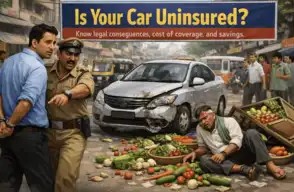

Real Challenges in Rural Insurance Penetration

Product-related: There is a mismatch between the products offered and rural needs. Many products are designed for urban markets, with features and benefits not suitable for agriculture or low-income communities. The lack of innovation in most microinsurance products fails to address short-term risks associated with small premium ticket sizes (e.g., illness for daily wage workers, weather shocks, and several livelihood assets related). There is limited flexibility due to rigid terms, exclusion clauses, and documentation requirements (ID, address, income proof), which exclude large rural populations.

Pricing-Related: An affordability gap exists because rural incomes are often irregular, seasonal, and mainly cash-based, causing poor alignment with annual premium structures. High distribution costs in remote areas increase expenses, but the low premium per policy reduces viability. Additionally, risk pricing is challenging because insurers lack detailed rural data, leading to cautious pricing that decreases product appeal.

Distribution-related: The last-mile network is usually weak. Agents/PoSPs prefer urban or semi-urban areas where ticket sizes and commissions are higher. There is also a trust gap because rural populations have low financial literacy and a history of mistrust due to delays or denial in claim settlements. Although smartphone use is increasing, connectivity issues, language barriers, and a lack of technological skills still hinder progress.

Efforts Needed to Boost Penetration

Product Innovation: It involves creating simple, need-based micro-insurance options that cover health, crops, weather, and assets such as livestock, bicycles, or small shops within an affordable package. Parametric insurance includes weather, rainfall, or index-based policies that automatically pay out, removing the need for detailed claims assessments. Premiums aligned with seasons correspond to harvest periods or local festivals when cash flow is usually higher. Community or group insurance utilises SHGs, cooperatives, and farmer groups as policyholders to lower costs and foster trust. A faster claims process can be achieved through Aadhaar-linked bank accounts, satellite data, and mobile photos, enabling swift settlements.

Pricing Approach: A market-driven pricing strategy is essential, beginning with nil or minimal initial profit margins. Utilise freemium or subsidised models through partnerships with government schemes like PMFBY and Ayushman Bharat to help subsidise premiums. Offer flexible premium collection options via monthly or quarterly micro-premiums through UPI or mobile wallets, making it easier for insureds to make regular payments. Implement usage-based models for assets such as tractors, implements, and equipment, where insurance covers seasonal use instead of fixed rates year-round, reducing costs and potentially increasing insurance adoption. Facilitate cross-subsidisation within portfolios by allowing profitable urban products to subsidise low-ticket, high social-impact rural products.

Distribution Strategies: Utilise local networks such as SHGs, PACS, FPOs, dairy cooperatives, and panchayats as partners for distribution and services. Engage rural banks and RRBs for bancassurance because of their broader reach and trust within these communities. Implement a hybrid model that combines digital and face-to-face methods, leveraging mobile onboarding supported by village-level entrepreneurs or agents. Incorporate embedded insurance by linking it with loans, agricultural inputs, seeds, fertilisers, tractors, or mobile recharges. Encourage rural agents with higher commissions, training, and technological assistance to strengthen rural enterprises.

Bottom Line:

Rural insurance penetration remains low due to several factors. Products typically cater to urban areas, but prices often fail to account for irregular income cycles, and distribution channels lack local trust and durability. True innovation involves “designing for rural first” — merging risks, aligning premium cycles with cash flows, integrating insurance into existing ecosystems, and building trust through local partners and faster claims processing.